‘Summer’s surely really all about an imagined end.We head for it instinctually like it must mean something. […] Like there really is a kinder finale and it’s not just possible but assured.’

These thoughts flicker through Grace’s mind towards the end of Ali Smith’s Summer. The year’s 1989, the Second Summer of Love, and our future mother of two is then a young actor out for a wander, hoping to find in the bounteous weather outside some escape from the drama of her own love life. Instead, a Nick Drake song lures her to a church, where she meets a man restoring a pew, reads a poem etched on a nameless gravestone, and helps age the repaired wooden seat. In that uncomplicated resolution to Grace’s emotional struggle Summer teaches us two things.There is a possibility of peace in things as small as a chance encounter and the idiosyncrasies of an old church. And if you were expecting this to be the end you haven’t been paying attention.

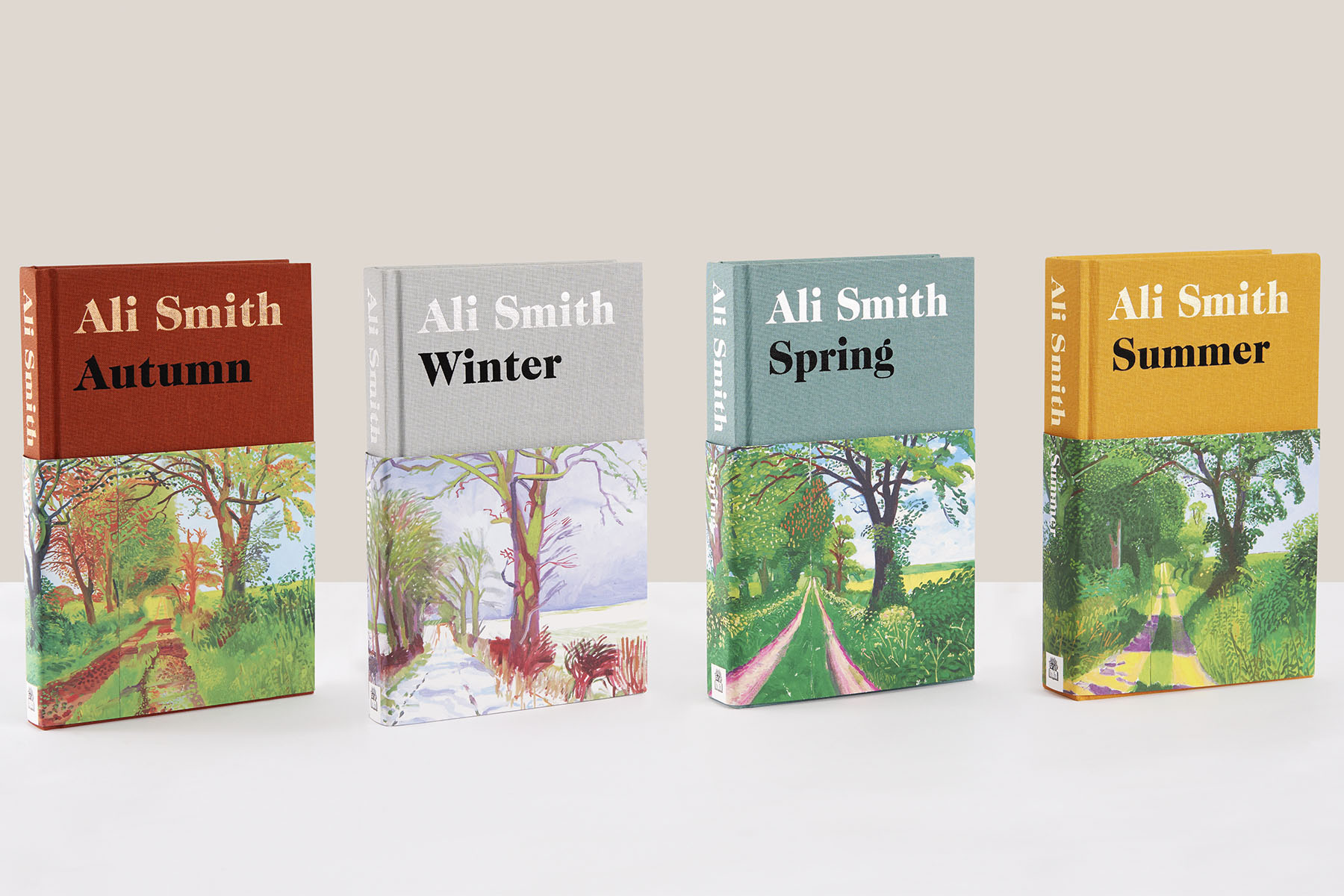

Summer is the concluding volume in Smith’s Seasonal Quartet, a project started partially in response to the Brexit referendum in 2016. The intent: to tell ‘an old story so new that it’s still in the middle of happening, writing itself right now with no knowledge of where or how it’ll end’. A story about time and memory, about Brexit and Britain, about Shakespeare and a whole host of visionary female artists. A story, as it turned out, about Trump and the Grenfell Tower fire, about Covid-19 and the George Floyd protests.

No matter the actual state of the nation, the best and worst of times have long been a literary obsession: Dickens was serially publishing Bleak House in 1852–3, Eliot Middlemarch in 1872, Trollope the aptly named The Way We Live Now in 1875. Yet if some have bemoaned a lack of such novels from British writers more recently, have yearned for a local response to Roth’s American Pastoral or DeLillo’s Underworld — never mind the publication of novels such as Zadie Smith’s White Teeth in 2000 or McEwan’s Saturday in 2005 — then Smith’s recent efforts should more than satisfy. The state-of-the-nation novel has come in many forms, from serialized behemoth to self-contained three- hundred-pager, it has exuded in the minutia of life and lost track of its characters in its own schematic concerns. Inevitably, some have worn their ambitions as a drowning man would an anchor, others found in the scaffolding of its scenes a higher vantage point from which to survey the land. Even among the latter, Smith’s achievement with the Seasonal Quartet is unprecedented.

A story about time and memory, about Brexit and Britain, about Shakespeare and a whole host of visionary female artists. A story, as it turned out, about Trump and the Grenfell Tower fire, about Covid-19 and the George Floyd protests.

To begin with, it would be a disservice to ignore how different the Quartet’s production has been to everything that preceded it. Bleak House depicts events set two decades earlier, Middlemarch roughly four. Saturday may seem like a quicker turnaround, coming out only four years after 9/11 and two years after the invasion of Iraq, but that is a veritably glacial pace compared to Smith’s Autumn hitting the shelves a mere four months after the Brexit referendum. Thirteen months later and bookshops would be graced by Winter, sixteen more and it would be Spring’s turn. Had Summer arrived on its original release date the whole endeavour would have been completed in a bit more than four years. As it stands, with an actual release on 6 August, it did so in under four and a half.

This delay allowed Smith to incorporate — among other developments — what the novel’s blurb refers to as ‘the real meltdown’: the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic. A draft of Summer likely exists where this was not the case, where the official departure of the UK from the European Union is the putative climax. As with so many other plans this year, Smith’s had to adapt, and it’s to her credit that the experience is incredibly smooth, the ghost of that alternative draft hardly imaginable in the final version. As with history, even the most unexpected developments become familiar, almost logical in retrospect, and one can only imagine how many times Smith has needed to react to events as they developed over the course of these past four years. A story still in the middle of happening, indeed.

As far as stories go, it’s a sizeable one too. At 1297 pages, the Quartet may seem a daunting prospect, but spread out in four volumes it remains remarkably accessible, thanks largely to the gentle trance Smith’s prose inspires. Similarly, it is not strictly necessary to read any of the other volumes in order to appreciate a particular season, though familiarity with the accompanying novels helps them transcend their boundaries. Still, none of that in and of itself — the promptness of its release, the speed of its writing, its intimidating length, or separation into volumes — would be particularly impressive for their own sake. It would not mean a thing, if the Quartet itself were not a hypnotic masterpiece.

When writing on the state of the novel in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Jonathan Coe — who wrote his own state-of-the-nation novel in 1994 with What a Carve Up! — mentioned a need to move beyond ‘the 19th-century model’, highlighting how ‘[i]t induces the stolid consolation of closure and catharsis and I’m beginning to think that these are not what our present difficulties require’. One must imagine Coe happy, then, that Smith has chosen to chronicle our troubled times with her modernist sensibilities and postmodern humour.

Puns abound, as do a variety of diegetic and narrative modes. From the surreal dreamscapes of Daniel’s coma in Autumn to the artistic journal entries of miraculous Florence in Spring, from the eeriness of the floating head haunting Sophia in Winter to the epistolary communications between Sacha and Hero in Summer. The scope of references is similarly broad. The Shakespeares: The Tempest in Autumn; Cymbeline in Winter; Pericles in Spring; The Winter’s Tale in Summer. The respective patron saints, so to speak: pop artist Pauline Boty; abstract sculptor Barbara Hepworth; visual experimenter Tacita Dean; and avant-garde filmmaker Lorenza Mazzetti. And of course, all the history, from the Battle of Culloden in Spring to the Profumo affair in Autumn, the Greenham Common’s Women’s Peace Camp in Winter to the Isle of Man’s Second World War internment camps in Summer.

All a bit much, one might imagine, and when listed like that it may seem impossible for all these dots to meaningfully connect, to somehow coalesce into a sensible and understandable form. Yet that is both the crux of it and entirely beside the point. As Art(hur), a nature writer, expounds in Summer, art is ‘something to do with coming to terms with and understanding all the things we can’t say or explain or articulate […] even at times like this when feeling and thinking and saying anything about anything are under impossible pressure.’

A noble sentiment, but how successfully does Smith’s Seasonal Quartet accomplish this? Entire PhD dissertations could — and likely should — be written on just the Shakespeare references, let alone the Dickens ones, which are similarly pervasive if less diagrammatic. In the meantime, a particular moment from Spring provides a framework for understanding not just what the Quartet is doing, but how Smith undertakes it.‘What if, [Florence] says. Instead of saying, this border divides these places. We said, this border unites these places.’

Perhaps too naive an ideal for our jaded age, though surely some forgiveness is earned by the fact this it is expressed by a twelve-year-old girl with the seemingly magical power of walking into a refugee detention centre and convincing the administration to properly clean up their bathrooms. As a character, Florence often serves to reset people to a more inherently human mode of existence, one where the limitations imposed on them by their personal economics and institutional commitments are treated as the immateriality they essentially are.

Enter, then, Robert, Summer’s own prodigious child—a Smith staple if there ever was one — only unlike Florence or even his environmentally minded sister, Sacha, this is a boy whose history of being bullied has hardened him into a supercilious proto-Boris Johnson.The boy’s shock tactics range from the relatively harmless—turning their old TV on to a very loud volume and shipping the remote to Desolation Island in Antarctica using part of his father’s stamp collection — to the downright horrifying – saying women ‘are only useful for sex and having children, especially children you don’t admit to having, because being a man is all about spreading your seed’ at school. Although Robert has clearly internalized the idea that offence is the best defence, underneath all his cynicism and ill will are shards of a kinder self, one obsessed with words and science, who worships Einstein like no other. ‘[T]he only real religion humans can have,’ Robert paraphrases in conversation with Autumn’s Daniel, ‘is the matter of freeing ourselves from the delusion first that we’re separated from each other and second that we’re separate from the universe.’

Now,one can look at these two ideas, borders uniting and Einstein’s freedom, and consider them distinct notions, wholly separate statements that could only be made to relate through an excess of interpretive bias. Summer itself opens with this idea, the dreadful power of those who say So?, who disavow arguments, statistics and even history with a sheer preference for indifference. But if one is willing to engage, to follow Florence and Einstein’s ideal, to see the space between not as separation but as union, then one may finally start to fully grasp the scope of Smith’s Seasonal Quartet. It does not hold forth on such a richness of topics to obfuscate or patronize, but rather to offer the reader the cognitive space with which to break those boundaries.

At the core of the Quartet’s success is how Smith not only leaves enough such readerly spaces but also draws sufficient connections so that one is encouraged to sketch out patterns of their own design. In practice, this works a bit like Smith’s puns: the reader is so bombarded by her playful ways their brain is trained to look for connections everywhere. So when Winter brings up that Sophia’s name means wisdom, and then that her sister Iris called her Philo not in the reference to philosophy but to the airy quality of filo pastries, you cannot help but notice the further echo when in the middle of an argument Iris calls Sophia a sophist.There are layers upon layers of meaning there, softly buttered in humour. All puns very much intended.

The same occurs at a larger, more abstract scale in the Quartet. There are, naturally enough, all the connections between the characters in each novel, introduced first tentatively in Winter but then more clearly in Spring and almost overwhelmingly in Summer. Thus we discover that Winter’s Arthur is secretly the son of Autumn’s Daniel, that Spring’s Richard is Autumn’s Elisabeth’s father. The connections multiply, to the point where even talking about any particular character belonging to a single novel becomes senseless. It hardly matters that one first meets Hero from Brit’s perspective in Spring before he becomes Sacha’s penpal in Summer. Any straightforward chronology or temporal causality is sundered, revealed as no more than an illusion.As Daniel says,‘[t]ime travel is real […].We do it all the time. Moment to moment, minute to minute.’

Yet that is not all, for we also do it in our memories. We do it through fiction, and then through the memory of fiction — or, Smith might add, the fiction of memory. Moments in the Quartet, but more noticeably so in Summer, hint towards that transcending power. Take, for example, when Daniel’s sister, Hannah, mistakes a stranger for her brother: ‘Of course it’s not her brother. That’s obvious almost immediately. / But there is a fragment of a second when her brother was there in front of her even though he wasn’t, isn’t […]. / It’s so nice to see him! / Even though it’s not him.’ Her joy at that moment of reconnection is real, as is Daniel’s, almost eighty years later, when he mistakes a visiting Robert for a returned Hannah.

This is treated not so much as a delusion from the century-old man as a higher truth, for there are a variety of ways—from their prodigious intelligence to snarky sense of humour—in which Robert and Hannah are rather similar. What is questioned here is not the very nature of reality, but our identification of it. Throughout the Quartet characters complain about the seasons, yearning for ‘the essentiality of winter, not this half-season grey sameness’, or then claiming a season to be ‘[o]ne of the worst springs I can remember’. Yet despite all that they continue to identify the seasons as a cycle. Even a bad summer is still summer, regardless that it ends every time, as all seasons do, as all seasons must. That which Daniel loved in Hannah is present in Robert, whatever else may have been lost or added to the mix. Robert himself puts it perfectly when he asks ‘What if you’re a mix of all the things. And it’s not possible to be just one of them?’

This notion of cyclicity, of intermingling, of the borders uniting is reinforced by the very structure of the quartet. Summer, culminating as the novel may be, is neither an end nor a beginning. One might as well follow it up with Autumn, and then Winter, Spring, all over again. Cycle through the seasons, and accumulate their meaning. For all the clear political references, the to-the-moment nature of the Quartet, it re-establishes the old adage of art touching the universal, not merely on an aesthetic level but a structural one. In talking about Brexit it evokes both the Scottish referendum that shortly preceded it and the Acts of Union from 1707. In enquiring about the refugee crisis it reflects the displacements and horrors of the Second World War. In depicting the climate crisis it ponders on anti-nuclear activism. Above all, it connects. Through wordplay and coincidence, through intertexts and echoes. Through a love of words, of art, and yes, of people. Whatever daunting questions it asks about how we ‘come to understand what time is, what we’ll do with it, what it’ll do with us’, it ultimately has the foresight to remind us that the way to handle the seasons’ passing, or to write a novel, or simply to live in a world insistent on tearing itself apart remains the same: ‘You have to go with it and make something of what it makes of you.’ ◊