I can’t remember when I first decided to leave London. I’d lived in the city for nearly a decade, moving from one distant part of town to another, with little more than a few bags of books and some increasingly threadbare sets of clothes to call my own. And yet I’d bought into the mantra that was drilled into me from a young age: ‘Move to the capital! Find new opportunity! Become the Dick Whittington of our times! RUN FOR MAYOR!’ Or perhaps the last part was just a Boris Johnson-influenced fever dream, as I awoke once again in some new and, as usual, uncomfortable bed on the outer reaches of the Tube line.

Yet what bothered me much more than the interminable commute to whichever pointless job I was doing, or the casual irritations of queuing for half a lifetime to buy bread, was the propaganda being screamed at me by the dual titans of London print media, the Evening Standard and Time Out. ‘It’s fine to put up with massive inconvenience and expense! You live in the best city in the world! Everything that you do contributes to that!’ And I listened to it, and believed it, for many years. And then another day, I stopped believing it, and made plans to leave – plans that, at the time of writing this, are all but complete. The boxes are packed, the bags are full, the moving van negotiates its delicate way past a stream of true-blue Boris bikes. And I never did run for mayor.

In this, as in so many other regards, I resemble my spiritual forebear John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester, who took a similarly jaded attitude towards London and those who sought to extol its virtues. When Charles II regained the crown at the Restoration of 1660, he and his more savvy counsellors were all too aware that the cheering and clamouring for his return was only superficial, and that the nascent public-relations machine of the day had to present England as the most forward-looking country in Europe, London as its greatest city, the royal palace of Whitehall as its epicentre, and Charles as its suave and all-conquering figurehead. Perhaps needless to say, this did not last. Whitehall, home of princes and politicians alike, soon became synonymous with sexual shenanigans and general corruption, where anyone could grow fat and debauched on favour if they so chose, as long as they added their voice to the chorus of praise in favour of London, Whitehall and Charles.

Rochester did not. While he arrived at court in 1665 in excellent standing with the king, in no small part because his late father Henry had helped the then prince to escape after a catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, he soon set about causing trouble. If he wasn’t causing scandal by attempting to abduct his future wife, Elizabeth Malet, or causing a diplomatic furore by starting a fight in front of the Dutch ambassador, he was watching the increasingly dismal world of court politics and carnal abandon with a cynical detachment that he poured out into both letters to his intimate drinking cronies, and, increasingly, in poetry that moved seamlessly between scatological prurience and elegantly witty dismissal of the world in which he found himself.

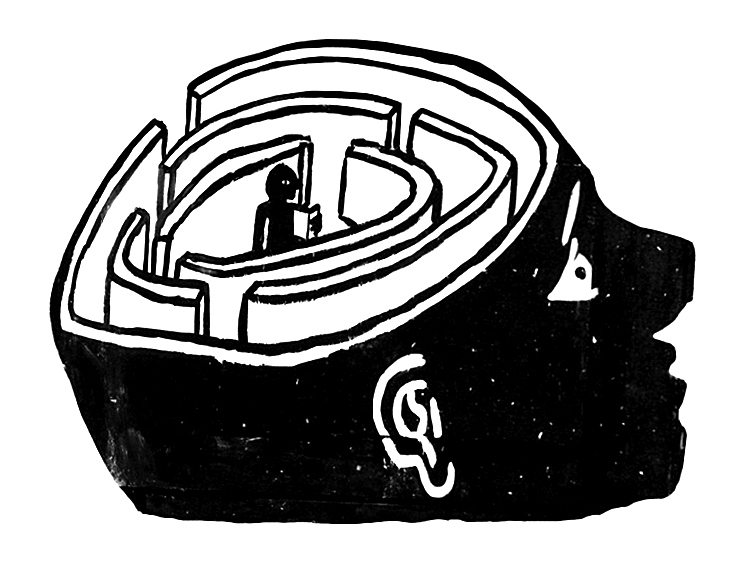

Never a fan of Whitehall, he wrote in one letter to his ‘lewd, good-natured friend’, the Falstaffian rake Henry Savile, that ‘you … think not at all; or, at least, as if you were shut up in a drum, as you think of nothing but the noise that is made upon you’. Rochester claimed to desire the ‘competent riches’ that would be attendant on this position, but the letter clearly comes from a bored, lonely man, who laments ‘the inconveniences of solitude’ and finds himself caught between the Scylla of empty chatter at Whitehall and the Charybdis of tedium in the country. His means of dealing with this frustration and boredom was to write the poem that became his masterpiece, ‘A Satire against Reason and Mankind’, which remains one of the best attacks on politicians ever penned.

Inspired by his loathing of the hypocrites and knaves who surrounded him, as well as an intellectual curiosity that had seldom been allowed full rein in his poetry before, Rochester aimed to show his friends (and enemies) that he was a serious and considered thinker, rather than simply a rake-about-court. Mixing his customary wit and intellectual clarity with anger and passion, Rochester’s 221-line poem is believed by many to be his greatest and most enduring work. When it circulated around court in both its forms, it was ascribed to ‘a person of honour’, a wittily double-edged attribution that became more telling when the satire was read.

As he wrote it, England was in a state of flux. With the country all but bankrupted by the failures of the Anglo-Dutch wars, there were many politically unaffiliated men and women who quietly regretted that the stringent morality of the Commonwealth had been replaced by such profligacy. The joy and optimism of the Restoration had given way to a growing sense that Charles II had no clear idea how he wanted to govern the country. As he and his familiars devoted themselves to a life of sexual and sybaritic abandon, they might as well have existed on the moon for all the good that they did for an increasingly weary, impoverished and put-upon populace. The growing instability of the so-called ‘Cabal’ government of Buckingham and the king’s other high councillors, which fell in September 1674, meant that Buckingham and Charles’s old tutor Hobbes’s earlier fears that life would become ‘solitary, poor, brutish, nasty and short’ without the strong presence of a committed sovereign seemed on the verge of realization.

Be judge yourself, I’ll bring it to the test:

Which is the basest creature, man or beast?

Birds feed on birds, beasts on each other prey,

But savage man alone does man betray.

Pressed by necessity, they kill for food;

Man undoes man to do himself no good.

Betrayal was something much on Rochester’s mind at this time. He considered himself, and the country, betrayed by Charles’s unwillingness to adopt the high moral standard of kingship, just as he felt snared by the foolishness and foppery of the court. He had been betrayed by everyone from the low tarts who had given him syphilis to the great men of Whitehall such as John Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave, who blackened Rochester’s name at the slightest provocation, all the while feigning amity and fellowship. No wonder that he wrote, ‘But man, with smiles, embraces, friendship, praise / Inhumanly his fellow’s life betrays’, given the double-dealing that he was privy to.

It was this loathing of the venal, self-satisfied nature of what mankind represents on the wider scale that led him to write this poem. It’s an impressively clear-sighted cry of anger:

For which he takes such pains to be thought wise,

And screws his actions in a forced disguise,

Leading a tedious life in misery

Under laborious, mean hypocrisy.

Look to the bottom of his vast design,

Wherein man’s wisdom, power and glory join:

The good he acts, the ill he does endure,

’Tis all from fear, to make himself secure.

Merely for safety, after fame we thirst,

For all men would be cowards if they durst.

It is hard to think of any of his court contemporaries producing such a simultaneously nihilistic and intellectually sophisticated attack on their world. Although he had often been caustic and dismissive in his poetry before, nothing comes close to the way in which, in this poem, he gazes on the entire Whitehall society that he was part of, and finds nothing there to praise or extol, merely a gaggle of frightened hypocrites in roles that they were ill-equipped to play, in their ‘forced disguise’. Rochester, himself less a phoney actor than a chameleonic performer, could tell an unconvincing line reading or intonation when he heard one.

He ends the main body of the poem by comparing the cowardice that permeates mankind with the essential dishonesty that goes hand in hand with it, describing all politicians as knaves, and using a cynical examination of human nature to justify the comparison, saying, ‘if you think it fair / Amongst known cheats to play upon the square / You’ll be undone.’ As ever, Rochester writes with an eye on the fluidity of truth and integrity. As he says:

Nor can weak truth your reputation save:

The knaves will all agree to call you knave.

Wronged shall he live, insulted o’er, oppressed,

Who dares be less a villain than the rest.

In a later addition to the poem, Rochester acknowledged that there might, conceivably, be someone who was indeed ‘less a villain than the rest’, but still believed that the odds were against it:

But if in Court so just a man there be

(In Court a just man, yet unknown to me)

Who does his needful flattery direct,

Not to oppress and ruin, but protect

(Since flattery, which way so ever laid,

Is still a tax on that unhappy trade);

If so upright a statesman you can find,

Whose passions bend to his unbiased mind,

Who does his arts and policies apply

To raise his country, not his family,

Nor, whilst his pride owned avarice withstands,

Receives close bribes through friends’ corrupted hands.

Rochester explicitly sets the action of this part of ‘A Satire’ at Whitehall, concentrating on a milieu that he knew and understood intimately. It is here that it is accepted that flattery must always be ‘needful’, rather than offered indiscriminately, and that a just man’s ‘unbiased mind’ will use this flattery for national, rather than personal, gain. The last ‘decent’ man at court, the exiled Earl of Clarendon, was not immune to feathering his own nest, thereby attracting a decree of opprobrium that his enemies thrived on.

This fantastical figure, then, seems slightly less likely to have existed in court than an eighteen-year-old virgin. For Rochester, the world in which he lived was essentially rotten, with even the best of men compromised and dedicated to little more than self-interest. His fantastical creation of a good statesman remains safely fictional. ‘A Satire’, in its extended form, remains a coruscating attack on Rochester’s world, but also on the nature of intellectual and social achievement, reducing it to nothing more than puffed-up vanity and grubby cheating. The final couplet accepts all this, wearily, leaving the reader with a devastating belittlement of what the political machinations of ‘reason’ and ‘mankind’ can ever aspire to:

If such there be, yet grant me this at least:

Man differs more from man, than man from beast.

When I was writing the introduction to my biography of Rochester, I heard Prime Minister’s Questions in the background, and wondered what that strange, braying sound was. Had a horde of donkeys escaped into the chamber? I glanced at the television, only to see two groups of indistinguishable middle-aged men howling at each other, banshee-like. Man did indeed differ more than man – Labour vs Conservative, UKIP vs Lib Dem, Mad vs Madder – than man from beast. And as I finished my packing and prepared to shake the dust of London from my feet, I hoped that my next berth would be an altogether less bestial one, and that Rochester, at least, would find himself nodding in approval.