Heroes: defiant, individual, courageous.

****

I have an ambivalent relationship to the things I love, to the heroes – the writers, artists, musicians – I worship. I skirt around them with some kind of discomfort. I close my eyes to the whole oeuvre: I like to leave something remaining, something unknown. I like to know there is something left over, something I have not yet encountered.

My hero-worship is sullen, blinkered – a little phobic. I don’t quite know why.

It might be because I want to save something for later – to eke a pleasure out.

It might be because I fear disappointment. Perhaps I have found the apotheosis of what they do – and so I fear the deflation of their work in encountering some inferior part of it.

****

Or it might be because the currency they deal in – the stuff of their work – is so challenging that I have to dispense it to myself in carefully controlled ways.

****

There is something about Kate Bush’s voice – her physical voice, as well as her voice in a literary sense – that has often struck me as heroic. Heroic because it is reckless, stubborn. She seemed to emerge, as a teenager, almost wildly confident, staggeringly daring. Her early, young voice has often been described as shrill. It has a bird-like clarity, but one tinged with a nasal overtone, which makes it both beautiful and slightly uncomfortable. But from the very beginning, her voice – again, both her actual voice and her literary, musical voice; the sensibility she offered up – were experimental, and utterly indifferent to audience. InThe Kick Inside, her 1978 debut album, she was already playing and teasing with what her voice could do. In ‘Wuthering Heights’, her lifelong flirtation with Elvis is already manifest: when she sings ‘Heathcliff, my only master’, her voice dips down and up again, and she fills the cavity of her mouth with air to hint at that Elvis tic which was itself a kind of flirtatious, camp reference to the swooping lines of an operatic tenor. (She has said of ‘King of the Mountain’, a song on Aerial, released in 2005, that addresses Elvis, she was trying to mimic aspects of his voice.)

In that first album, she was already pushing her voice, testing what it could do. The Kick Inside announced something crucial to Bush: her voice wears its body on its sleeve. You can hear the workings of her organs, the rearrangement of her component parts. In ‘L’Amour Looks Something Like You’, in her striving for the extremities of the her voice, she lets you hear its workings; in the swooping octaves – again, the operatic Elvis is here – you can sense her pushing down on her diaphragm; her voice alerts you to its physical labour. Kate Bush, from the very start, didn’t care how the experiments she enacted on her voice might be registered in the listener. She just played, and pushed.

****

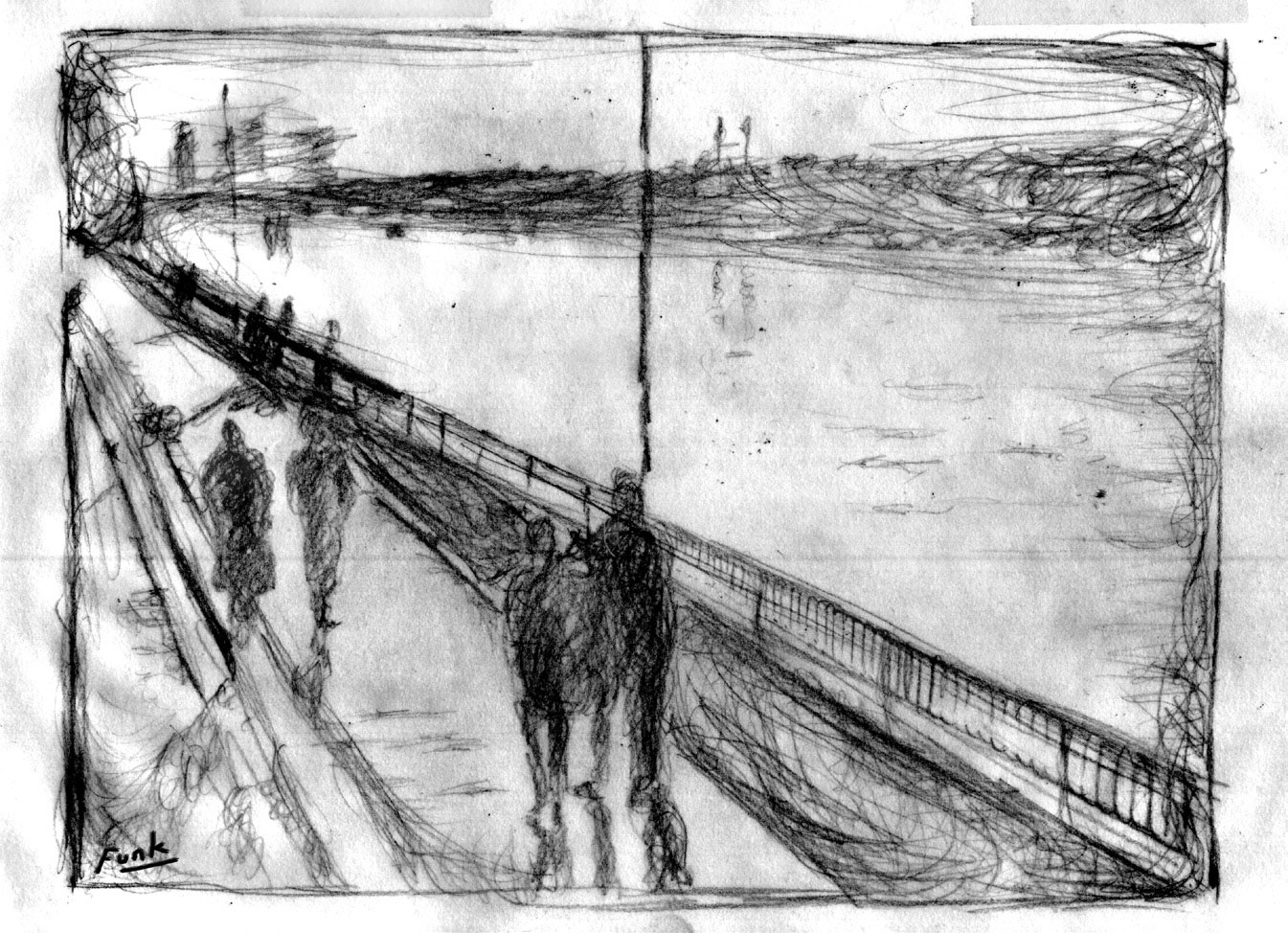

But then heroes can also be demigods, belonging in two worlds at once (at least). Partly here, partly elsewhere; made up of many things, human, animal, divine. Liminal, crossing thresholds.

****

Bush’s work is full of transformations, of metamorphoses. She is animal and bird and woman and child and man all at once. These things erupt out of her across all the albums. Her voice is hysterical, malleable, the stuff of dreams but also of nightmares. She pushes it to the edge of discomfort. It is immensely playful, and it’s also somewhat frightening.

There is something about Kate Bush’s voice – her physical voice, as well as her voice in a literary sense – that has often struck me as heroic.

In ‘James and the Cold Gun’, still in that youthful Kick Inside, a repetitive background riff towards the end of the song – something like ‘Ja-Ja-Ja-mes-a-hee-ya’ – in a high-pitched voice that rises halfway through the phrase to a peaking, slightly disgusted squeal. It is as if she feels unwell and also has her teeth bared. In ‘Them Heavy People’, she sings ‘Rollin-a-rollin-a-rollin-ah’ and again she becomes, for a second, a strange creature making a not quite human sound. She is not fully animal. But if she is fully human, she is slightly demented. Somewhat possessed, though it’s not clear what by.

The playfulness, and the metamorphoses, find their most intense fruition in The Dreaming of 1982. Here, her voice plays with persona, and with gender – for instance in ‘There Goes a Tenner’, where a girly ‘oh oh oh’ is in counterpoint with a more masculine, again Elvis-y, ‘We’re waiting’. In ‘Sat in Your Lap’ she is in distinctly ironic mode, dramatizing herself: ‘Just when I think I’m king, I must admit’; you can hear a self-mocking expression wrap itself around her mouth. This album sees her stretching her voice in ways that are almost frightening: who is she? King, not Queen. Whose voice is this?

Bush was experimental with form, with extraordinary instrumentation and orchestration, but also with the core of her voice itself. She is interested in what a voice is, and what it can do. She uses her voice like an instrument to rend and tear, to sometimes painful effect. There are places where she inhabits a deeply uncomfortable space between singing and screaming – in ‘Suspended in Gaffa’, and ‘Leave It Open’, where she becomes a rabid, masculine machine, spitting out the word ‘harm’. And then, just when you think the song has become as strange as it could be, she pushes it further; she becomes animal: a donkey – and else- where on the album, a herd of sheep.

In ‘Houdini’, she sings yet again on the raspy, uncomfortable edge of her voice, before it reaches a scream. It’s painful, you almost want her to break into a full scream – it would be a release. This nearly happens in ‘Get Out of My House.’ And yet it’s not quite there; it’s profoundly ambiguous. The threat of disintegration, however, is always there, hovering flirtatiously, dangerously.

****

The kind-of-scream is something Kate Bush has in common with Prince, who worked on her 1993 album The Red Shoes. Prince loves to scream – he really loves to scream – and he does so to electrifying effect in ‘Purple Rain’ and ‘The Beautiful Ones’. Like Bush, he uses the entire scope of his voice as an instrument: to play, and almost to abuse. They are both fearless with respect to the strangeness and power of the human voice – as a physical phenomenon, a tool that can produce sounds, but also as a means of conveying something, in particular the beauty of what is frightening, what is unpleasant.

Kate Bush and Prince both do this harmonically, structurally, instrumentally and rhythmically. Their music is full of rupture, of abrupt shifts, of irresolution. They embrace the form and want to test and break it at the same time. They tease you with pure pop conventions, which they then pull into painful corners. If pop is their material, they lean in against it, hard. When I listen to ‘Purple Rain’, to ‘U Got the Look’, to ‘Let’s Go Crazy’, to ‘Little Red Corvette’, I see fabric being torn, pulled, stretched; I feel something being wrung out of something else. It’s exhilarating, and it’s almost too much.

****

Listening to Purple Rain and The Dreaming again, writing this, I remembered some words from Richard Holmes’s Footsteps: Adventures of a Romantic Biographer, where he describes his journey as a young man through France, retracing R. L. Stevenson’s own steps:

I woke at 5 a.m. in a glowing mist, my green sleeping-bag blackened with the dew, for the whole plateau of the Velay is above two thousand feet. I made a fire with twigs gathered the night before, and set water to boil for coffee, in a petit pois tin with wire twisted round it as a handle. Then I went down to the Loire, here little more than a stream, and sat naked in a pool cleaning my teeth. Behind me the sun came out and the woodfire smoke turned blue. I felt rapturous and slightly mad.

In Prince’s music, pleasure becomes pain; and pain, pleasure. In Kate Bush’s, what is human is animal; and animal, human. Madness, moreover, is pleasure, and pleasure almost mad. These states are never far away from one another; and in this alarming, demanding music, the pleasures and the frustrations of trying to express ourselves – the unsettling places inside us, and the transformations that can happen there – are at the centre of the work. It’s what makes the music never-ending, never closed, an entirely open system. It’s what makes it rapturous and slightly mad.