On the day that the gifts were handed out the blackthorn was late. By the time it got there, the gate was shut and a sign had been put up saying ‘Creation complete’. The blackthorn considered leaving a note on the gatepost, but decided there wasn’t much point. Back then, all the trees were stemmy and green and unformed, and the blackthorn was happy as it was. So it went back to the woods and thought no more about it.

As time passed, and winter became spring and spring turned into summer, it became clear to the blackthorn that all the other trees had something about them that people loved. The beeches and oaks were the best trees for climbing, and some small child always seemed to be hauling itself up into their branches. Other children ran to hide within the encircling fronds of the weeping willow. The slender silver birch was undeniably sexy. The aspen had a fragile, trembling thing going on. People were forever setting up their easels in front of a flowering wild cherry. The sweet chestnut had its conkers, the oak its cute acorn cup-and-saucer routine, the sycamore its clever-clogs helicopters. But what did the blackthorn have? Bare stems, and short ones at that.

The tree grew more and more depressed. Its stems began to blacken and turn inwards. On windy days, the other trees heard its dry, grieving rattle.

‘No children,’ said the rattle. ‘Not tall like other trees.’

A breeze rippled the handsome leaves of the maple. ‘Ahem – tree, did you say? Tree? Thicket, surely.’

One blackthorn branch creaked against another.

Overhead, a eucalyptus fluttered its grey leaves to show their pretty white undersides. ‘Get over it,’ it tutted. ‘I didn’t get where I am today by whinging. I got here –’

‘In a trouser turn-up!’ bellowed a chorus of trees as the wind surged through their canopies. ‘Yeah, we know.’

The blackthorn listened to the waves of laughter, and a full understanding of genetic gifts grew inside it, of short straws and long straws, and the price you pay for being late. Bitterness mingled with its sadness, and the following year from out of this bitterness the blackthorn developed spines on its branches, strong enough to rip the shirt or skin of anyone who dared brush up against it. Another year it produced fat, purple berries so sour and astringent that anyone who tasted one immediately spat it out and turned away in disgust. Its branches became denser and denser, even tangled. The blackthorn was making things worse, but didn’t know how to stop.

But the blackthorn didn’t care. It had eyes only for the little girl.

‘Keep away from that tree,’ the blackthorn heard a mother say to her little girl, one cold-snap day towards the end of winter. A stubby, hard-bellied dog was sniffing around the blackthorn’s roots. ‘You too, Poppy, come away,’ she called to the dog.

The dog glanced up at the blackthorn, recognized another loser in the gene allocation game, then cocked its leg and let loose a warm stream against the tree’s trunk. But the blackthorn didn’t care. It had eyes only for the little girl. With her red hair streaming from under her Dublin-green hat – colours that the blackthorn had long admired in the holly – she was the most delightful creature it had ever seen.

‘This one?’ she asked her mother. She came and stood before the blackthorn, looking up at it with her open, enquiring face.

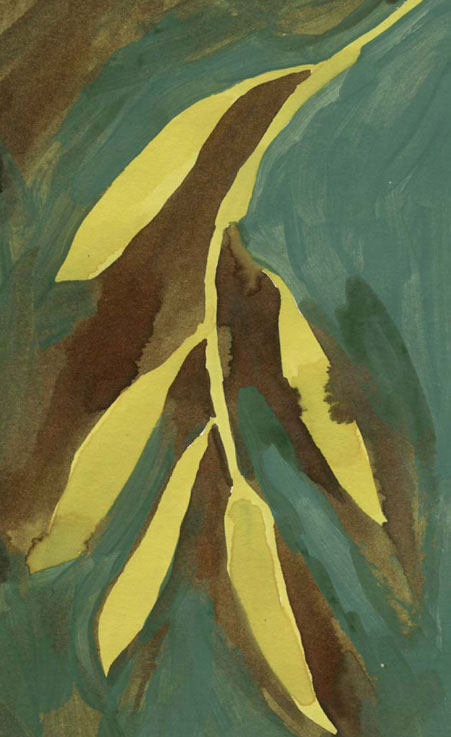

‘Yes, this one, this one,’ the blackthorn intoned in the language of trees, every woody fibre of its being bristling. As it drank in the sight of the little girl, all the longing and loneliness it had ever known welled and surged in its sap, from the ends of its roots up into the tough, unpliable rods that squeezed and stoppered its ardent soul. It wanted only one thing: to find something from deep within itself to hold this girl’s gaze, to spark her interest, her love, her joy – to make her come back, again and again. Something that wouldn’t tear at her tender skin, or dry out her tongue. Something from before the time when the gate had been closed, from when the blackthorn was young and new and existed simply of greenness and a hunger for water and light. From when it knew nothing of gifts that were bestowed and not bestowed. As the sap rose and swelled with in its stiffened branches, the tips of the blackthorn’s twigs burst into a sudden shower of tiny white flowers, delicate as stars. The effect was of a billowing cloud that, on this particular day – with winter on the back foot, but before spring had fully stepped in to take its place – was quite the loveliest thing in the woods.

As the sap rose and swelled with in its stiffened branches, the tips of the blackthorn’s twigs burst into a sudden shower of tiny white flowers, delicate as stars.

The girl smiled at the blackthorn’s blossom, her little face aglow with surprise, and for the next few weeks, whenever she came to walk in the woods, she drew her mother’s attention to the pretty tree with the flowers. In time the mother’s feelings towards the prickly blackthorn softened, and one day she even brought gloves and a pair of secateurs, cut a tall flowering stem with several offshoots, and carried it home to put in a vase. The blackthorn got to experience the downside of being loved, of one limb being brutally severed from another, the slow agony of dehydration; but it was worth it. And although today the blackthorn is still inclined to become somewhat gloomy over the winter months, it never fails to lift its own and others’ spirits when it comes into bloom very early in the spring. And on windy days, those who know the language of trees can make out its creaking, raspy saw from within the noisome orchestra of the woods.

Listen. Do you hear it?

That one.